What's up Doc????

Hello Beach Walkers.

How Snake Oil Became a Symbol of Fraud and Deception

Clark Stanley’s snake oil was a marketing gimmick from the very start.

In August 2024, after a series of far-right riots broke out accross the United Kingdom just weeks after the election of Prime Minister Keir Starmer, the newly elected leader didn't mince words when describing extremism across Europe. “I’m worried about the far right,” Starmer told the BBC, “because it’s the snake oil of the easy answer.”

The term “snake oil salesperson” has also been used in the 2024 U.S. presidential election by journalists and celebrities—on both sides of the political aisle—to describe the promises and claims being made by the candidates. Their criticisms imply that politicians are knowingly misleading the American people about their political views and plans if elected and spreading false or exaggerated claims to make their case.

In our modern-day vernacular, we can use “snake oil” to describe almost anything deceptively branded as a legitimate solution to a problem that ultimately doesn’t live up to its promise. At the height of the pandemic, experts described widely circulated yet unsubstantiated Covid-19 "cures" as “21-centure snake oil” Two renowned computer scientist also used the term in reference to those who make misleading claims about the capabilities of artificial intelligence in order to generate hype. The list goes on.

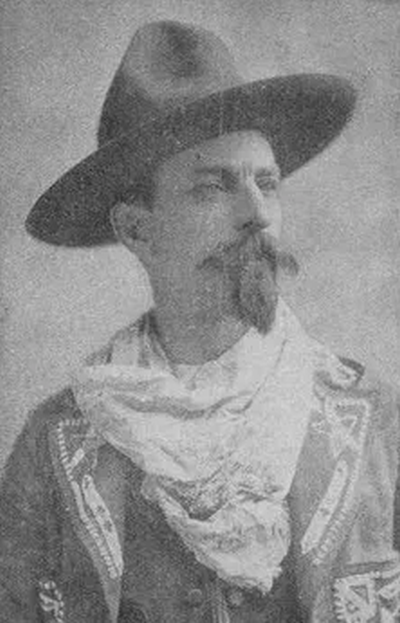

The history of snake oil as a symbol of fraud and deception dates to the late 19th and early 20th centuries. It’s widely connected to the story of Clark Stanley, the self-proclaimed “Rattlesnake King” who sold his so-called snake oil as a treatment for joint pain and rheumatism. In reality, his products contained no actual snake oil at all—just mineral oil, beef fat, red pepper adn turpentine. Yet he got away with deceiving his customers for more than two decades.

The term “snake oil salesperson” has also been used in the 2024 U.S. presidential election by journalists and celebrities—on both sides of the political aisle—to describe the promises and claims being made by the candidates. Their criticisms imply that politicians are knowingly misleading the American people about their political views and plans if elected and spreading false or exaggerated claims to make their case.

In our modern-day vernacular, we can use “snake oil” to describe almost anything deceptively branded as a legitimate solution to a problem that ultimately doesn’t live up to its promise. At the height of the pandemic, experts described widely circulated yet unsubstantiated Covid-19 "cures" as “21-centure snake oil” Two renowned computer scientist also used the term in reference to those who make misleading claims about the capabilities of artificial intelligence in order to generate hype. The list goes on.

The history of snake oil as a symbol of fraud and deception dates to the late 19th and early 20th centuries. It’s widely connected to the story of Clark Stanley, the self-proclaimed “Rattlesnake King” who sold his so-called snake oil as a treatment for joint pain and rheumatism. In reality, his products contained no actual snake oil at all—just mineral oil, beef fat, red pepper adn turpentine. Yet he got away with deceiving his customers for more than two decades.

The above three images are of Clark Stanley, the original snake oil salesman. The first image, the original I stole from the Smithsonian, is original. Second image is enhanced with AV photo enhancer and the third is colourized. It is amazing what you can do with old photographs now. I am not sure if the pink outfit has been correctly interpreted by the program.

Snake oil origins

Actual snake oil in the 1800s came from Chinese water snakes, and Chinese laborers who immigrated to the U.S. shared it with fellow workers as they helped build the transcontinental railroad. This type of snake oil, Pedersen says, was indeed an effective anti-inflammatory.

Actual snake oil in the 1800s came from Chinese water snakes, and Chinese laborers who immigrated to the U.S. shared it with fellow workers as they helped build the transcontinental railroad. This type of snake oil, Pedersen says, was indeed an effective anti-inflammatory.

Enter the mysterious Clark Stanley in 1893. Not much was known about his personal history or background when, donned in Western attire, he arrived at the Columbian Exposition in Chicago that year. It was here that Stanley first made his way into the public eye—at the same event where Pabst Blue Ribbon beer, the automatic dishwasher, and Wrigley's Chewing Gum all made their debut.

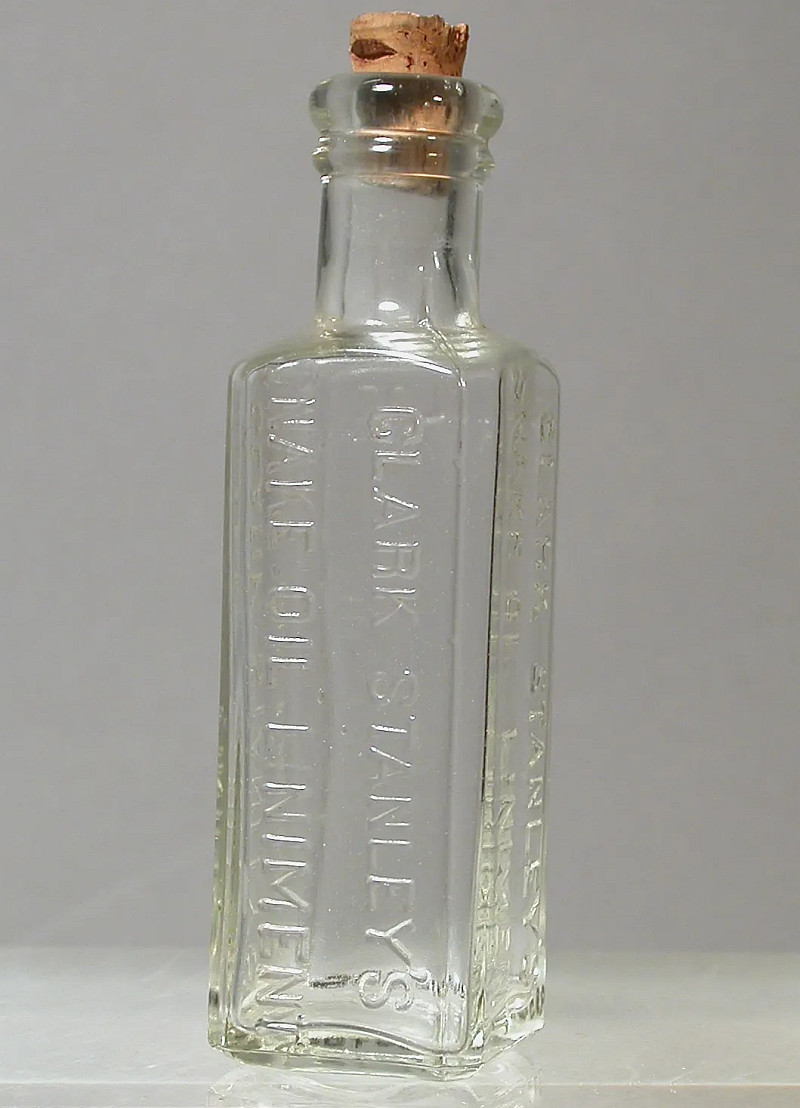

Standing on stage in front of a growing crowd, Stanley pulled a rattlesnake out of a sack resting near his feet. In dramatic fashion, he slit the rattlesnake open with a knife, placed the snake in a vat of boiling water, and watched as its fat rose to the surface. Stanley sold his product, dubbed Clark Stanley's Snake Oil Linement” in liniment jars, boasting about its healing powers.

Of course, Stanley’s snake oil was a marketing gimmick from the very start. For one thing, rattlesnakes have different fat profiles than Chinese water snakes. Plus, Stanley claimed at his 1893 show to have learned the mysterious healing powers of snake oil from the Hopi tribe, a statement that has gone unverified.

Stanley continued producing and selling what he claimed to be snake oil and went on to open two production facilities in Beverly, Massachusetts, and Providence, Rhode Island. However, the process of repeatedly taking fat from rattlesnakes proved cumbersome. After that first demonstration, Stanley removed any oil from snakes from his product altogether.

The era of patent medicines

As the “Rattlesnake King,” Stanley continued selling his so-called snake oil until 1917. At the time, laws and regulations regarding false advertising in medicine were nothing like they are today. Even the medical credentials of many practicing physicians wer nothing short of ambiguous.

In the late 19th century, while the medical community was advancing, it lacked treatments—like antibiotics—for most chronic and infectious illnesses as well as arthritic and rheumatic diseases, says Lydia Kang, Pedersen’s co-author.

That’s, in part, what led to the rise of patent medicines, which didn’t require a doctor’s prescription the record, usually weren’t actually patented). This made it easier for consumers to quickly get the medication they needed.

But the scientific community didn’t yet have concrete ways to prove which medicines were effective. And it was easy for consumers to fall into the allure of an attainable drug that would supposedly reduce their suffering. In reality, Kang explains, many patent medicines contained drugs like cocaine, morphine or alcohol, giving the illusion of an immediate soothing effect.

“You could just walk around the corner and buy something that was a little bit more affordable without having to see a doctor,“ says Kang, who’s also an associate professor of internal medicine at the University of Nebraska Medical Center. “You would see advertisements for them everywhere.”

Standing on stage in front of a growing crowd, Stanley pulled a rattlesnake out of a sack resting near his feet. In dramatic fashion, he slit the rattlesnake open with a knife, placed the snake in a vat of boiling water, and watched as its fat rose to the surface. Stanley sold his product, dubbed Clark Stanley's Snake Oil Linement” in liniment jars, boasting about its healing powers.

Of course, Stanley’s snake oil was a marketing gimmick from the very start. For one thing, rattlesnakes have different fat profiles than Chinese water snakes. Plus, Stanley claimed at his 1893 show to have learned the mysterious healing powers of snake oil from the Hopi tribe, a statement that has gone unverified.

Stanley continued producing and selling what he claimed to be snake oil and went on to open two production facilities in Beverly, Massachusetts, and Providence, Rhode Island. However, the process of repeatedly taking fat from rattlesnakes proved cumbersome. After that first demonstration, Stanley removed any oil from snakes from his product altogether.

The era of patent medicines

As the “Rattlesnake King,” Stanley continued selling his so-called snake oil until 1917. At the time, laws and regulations regarding false advertising in medicine were nothing like they are today. Even the medical credentials of many practicing physicians wer nothing short of ambiguous.

In the late 19th century, while the medical community was advancing, it lacked treatments—like antibiotics—for most chronic and infectious illnesses as well as arthritic and rheumatic diseases, says Lydia Kang, Pedersen’s co-author.

That’s, in part, what led to the rise of patent medicines, which didn’t require a doctor’s prescription the record, usually weren’t actually patented). This made it easier for consumers to quickly get the medication they needed.

But the scientific community didn’t yet have concrete ways to prove which medicines were effective. And it was easy for consumers to fall into the allure of an attainable drug that would supposedly reduce their suffering. In reality, Kang explains, many patent medicines contained drugs like cocaine, morphine or alcohol, giving the illusion of an immediate soothing effect.

“You could just walk around the corner and buy something that was a little bit more affordable without having to see a doctor,“ says Kang, who’s also an associate professor of internal medicine at the University of Nebraska Medical Center. “You would see advertisements for them everywhere.”

Based on the colorful advertising depicting smiling babies and their mothers, parents may have actually believed Mrs. Winslow's Soothing Syrup could calm their children, freshen their breath and relieve their constipation. Or that Dr. Kilmer's Swamp-Root could definitely cure their liver and kidney problems.

The outlandish claims of the ‘Rattlesnake King’

Clark Stanley wasn’t the only snake-oil salesman who sold products claimed to be made with oil from actual snakes, but he may very well be the best known of his time.

The outlandish claims of the ‘Rattlesnake King’

Clark Stanley wasn’t the only snake-oil salesman who sold products claimed to be made with oil from actual snakes, but he may very well be the best known of his time.

Why? To start, he was a brilliant self-promoter and marketer, starting with the uncanny story of his 1893 show at the Columbian Exposition. He also had “an eye for drama and a flair for the theater,” Pedersen says, and even published an autobiography in 1897. He ran a primarily mail-order business, Pedersen says, and once, when a reporter visited him in Massachusetts, Stanley stocked his office with snakes, if not simply to add a bit of pizazz to the encounter.

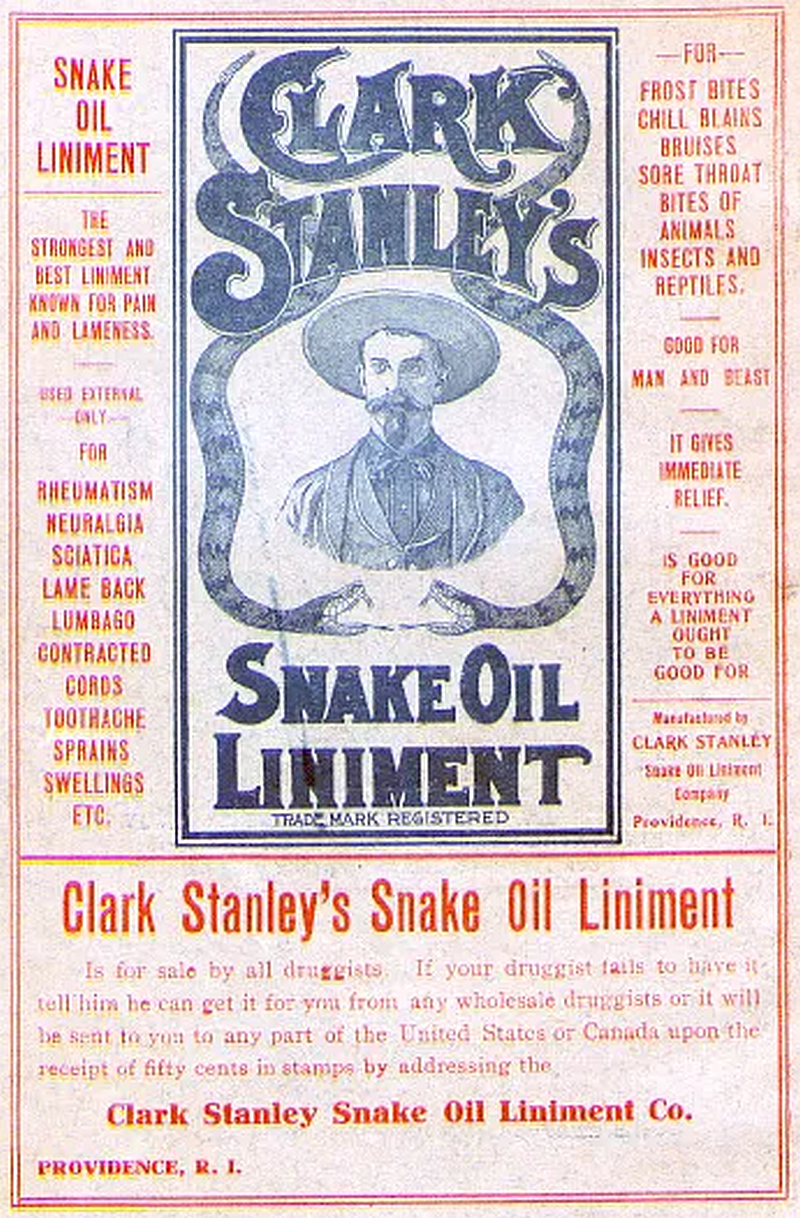

Though Stanley may have continued performing at some medicine shows—the Hartford Courant recounts one such event in the City Hall Square in 1902—he and other patent medicine sellers relied heavily on print advertising in newspapers and magazines to attract business.

In his adds, Stanley described his snake oil as “the strongest and best liniment known for pain and lameness,” providing “immediate relief,” “good for everything a liniment ought to be good for,” and usable for treating nearly everything—sciatica, sprains, animal bites, sore throat, toothaches, and beyond.

Clark Stanley’s downfall

Amid public concern about safety, along with the work of journalists and muckrakers who exposed corruption in the food and pharmaceutical industries, Congress passed the Pure Food and Drug Act in 1906 required druggists to clarify on labels whether medicines included any of 11 dangerous or habit-forming ingredients. It also established that drug-makers couldn’t make false or misleading statements on their packaging.

Still, Stanley wouldn’t face his downfall for more than a decade.

“How you enforce the act was problematic, in part because it left a lot of room for interpretation in terms of what was false or misleading in terms of statements that were made on packages,” says Eric Boyle, chief historian at the U.S. Department of Energy and former chief archivist at the National Museum of Health and Medicine, on the first step in combating medical quackery.

These challenges held true even after Congress passed the Sherley Amendment in 1912 to prohibit labeling medicines with false therapeutic claims with an intent to deceive the buyer. Again, this standard became difficult to prove, Boyle says; a seller could, in theory, simply argue they believed their product was effective, even if it wasn’t.

As new medicines scientifically proven to cure joint pain were introduced, federal investigators seized a shipment of Stanley’s liniment and analyzed the contents, only to discover in 1917 that it contained no snake oil at all. As the story goes, Stanley was fined $20 for violating the Pure Food and Drug Act. Without putting up much of a fight, Stanley paid the price, closed down shop and slipped away from the public eye.

Dissecting the term “snake oil”

Stanley—along with other medical fraudsters of his time—brought the terms “snake oil” and “snake-oil salesperson” into the mainstream vernacular.

“There was no evidence the [snake oil] did anything,” says Joe Schwarcz, a chemist and the director of HYPERLINK "https://www.mcgill.ca/oss/"McGill University's Office for Science and Society, which aims to combat scientific misinformation. “That started the whole business of calling ineffective substances ‘snake oil,’ and we still have that today.”

Why is “snake oil” so widely used? Perhaps because it’s a lively term that conjures up an obvious connotation of greed and harm, as well as fear, interest and deceit. “There’s kind of no mistaking when someone says it, what they mean; there’s no nuance in the term,” Kang says. “And I think it harkens back to a very long cultural history that’s very anti-snake.”

As the field of medicine and laws have evolved since the early 1900s, the battle against misinformation has persisted. The American Medical Association (AMA) has been at the center of this fight. In the early 1900s, the AMA formed a Bureau of Investigation—originally named the “Propaganda Department”—to expose and combat medical quackery, or the promotion of unsubstantiated or fraudulent health claims.

As new medicines scientifically proven to cure joint pain were introduced, federal investigators seized a shipment of Stanley’s liniment and analyzed the contents, only to discover in 1917 that it contained no snake oil at all. As the story goes, Stanley was fined $20 for violating the Pure Food and Drug Act. Without putting up much of a fight, Stanley paid the price, closed down shop and slipped away from the public eye.

Battling misinformation in medicine

The AMA’s newly formed department published articles, pamphlets, books and posters to help consumers separate quackery from legitimate information, Boyle says. Its staff also toured the country to deliver lectures and attend state fairs, and collaborated with government agencies like the Food and Drug Administration, the U.S. Postal Service and the Federal Trade Commission, in addition to state and local medical societies.

“They answered tens of thousands of letters from doctors and ordinary Americans who were looking for more information about a particular drug that they may have seen advertised in a magazine or newspaper,” Boyle adds.

Yet medical quackery continues to exist in various forms, and the spread of misinformation during the Covid-19 pandemic is among the most timely and notable examples. With so many unknowns as the illness spread across the U.S.—and without any proven treatment yet available—misinformation about the potential of drugs like hydroxychloroquine and ivermectin to combat Covid spread rapidly on the internet and social media.

“Within the internet, I think there are a lot of these closed spaces where people only look to reconfirm the biases that they want as opposed to getting all the information and trying to look at it in a very level-of-balance kind of way,” Kang says.

Separating fact and fiction.

Helping consumers separate sense from nonsense in health and medicine starts with education, and ideally, the strengthening of laws related to quackery and medical fraud, says Stephen Barrett, a retired psychiatrist and author who founded HYPERLINK "http://quackwatch.org/"Quackwatch.org, which aims to educate the public on health fraud, myths, fallacies and misconduct.

“It’s a good idea to try to bring up people who have the ability to determine what’s true and what isn’t, and to think logically,” says Barrett, who has been fighting against quackery for decades. Parents and schools can both play a role, he adds.

Today, there are still diseases for which the medical community simply hasn’t discovered cures. The multi-billion-dollar supplement industry exploits that same sense of fear and uncertainty that consumers faced in the late 1800s, Kang says.

“As long as that gap is going to be there, there is going to be quackery, and there is going to be snake oil,” Kang says. “And people just have to try as hard as possible to educate themselves and find sources where they can bounce things off of to make sure they’re not being victimized.”

Though Stanley may have continued performing at some medicine shows—the Hartford Courant recounts one such event in the City Hall Square in 1902—he and other patent medicine sellers relied heavily on print advertising in newspapers and magazines to attract business.

In his adds, Stanley described his snake oil as “the strongest and best liniment known for pain and lameness,” providing “immediate relief,” “good for everything a liniment ought to be good for,” and usable for treating nearly everything—sciatica, sprains, animal bites, sore throat, toothaches, and beyond.

Clark Stanley’s downfall

Amid public concern about safety, along with the work of journalists and muckrakers who exposed corruption in the food and pharmaceutical industries, Congress passed the Pure Food and Drug Act in 1906 required druggists to clarify on labels whether medicines included any of 11 dangerous or habit-forming ingredients. It also established that drug-makers couldn’t make false or misleading statements on their packaging.

Still, Stanley wouldn’t face his downfall for more than a decade.

“How you enforce the act was problematic, in part because it left a lot of room for interpretation in terms of what was false or misleading in terms of statements that were made on packages,” says Eric Boyle, chief historian at the U.S. Department of Energy and former chief archivist at the National Museum of Health and Medicine, on the first step in combating medical quackery.

These challenges held true even after Congress passed the Sherley Amendment in 1912 to prohibit labeling medicines with false therapeutic claims with an intent to deceive the buyer. Again, this standard became difficult to prove, Boyle says; a seller could, in theory, simply argue they believed their product was effective, even if it wasn’t.

As new medicines scientifically proven to cure joint pain were introduced, federal investigators seized a shipment of Stanley’s liniment and analyzed the contents, only to discover in 1917 that it contained no snake oil at all. As the story goes, Stanley was fined $20 for violating the Pure Food and Drug Act. Without putting up much of a fight, Stanley paid the price, closed down shop and slipped away from the public eye.

Dissecting the term “snake oil”

Stanley—along with other medical fraudsters of his time—brought the terms “snake oil” and “snake-oil salesperson” into the mainstream vernacular.

“There was no evidence the [snake oil] did anything,” says Joe Schwarcz, a chemist and the director of HYPERLINK "https://www.mcgill.ca/oss/"McGill University's Office for Science and Society, which aims to combat scientific misinformation. “That started the whole business of calling ineffective substances ‘snake oil,’ and we still have that today.”

Why is “snake oil” so widely used? Perhaps because it’s a lively term that conjures up an obvious connotation of greed and harm, as well as fear, interest and deceit. “There’s kind of no mistaking when someone says it, what they mean; there’s no nuance in the term,” Kang says. “And I think it harkens back to a very long cultural history that’s very anti-snake.”

As the field of medicine and laws have evolved since the early 1900s, the battle against misinformation has persisted. The American Medical Association (AMA) has been at the center of this fight. In the early 1900s, the AMA formed a Bureau of Investigation—originally named the “Propaganda Department”—to expose and combat medical quackery, or the promotion of unsubstantiated or fraudulent health claims.

As new medicines scientifically proven to cure joint pain were introduced, federal investigators seized a shipment of Stanley’s liniment and analyzed the contents, only to discover in 1917 that it contained no snake oil at all. As the story goes, Stanley was fined $20 for violating the Pure Food and Drug Act. Without putting up much of a fight, Stanley paid the price, closed down shop and slipped away from the public eye.

Battling misinformation in medicine

The AMA’s newly formed department published articles, pamphlets, books and posters to help consumers separate quackery from legitimate information, Boyle says. Its staff also toured the country to deliver lectures and attend state fairs, and collaborated with government agencies like the Food and Drug Administration, the U.S. Postal Service and the Federal Trade Commission, in addition to state and local medical societies.

“They answered tens of thousands of letters from doctors and ordinary Americans who were looking for more information about a particular drug that they may have seen advertised in a magazine or newspaper,” Boyle adds.

Yet medical quackery continues to exist in various forms, and the spread of misinformation during the Covid-19 pandemic is among the most timely and notable examples. With so many unknowns as the illness spread across the U.S.—and without any proven treatment yet available—misinformation about the potential of drugs like hydroxychloroquine and ivermectin to combat Covid spread rapidly on the internet and social media.

“Within the internet, I think there are a lot of these closed spaces where people only look to reconfirm the biases that they want as opposed to getting all the information and trying to look at it in a very level-of-balance kind of way,” Kang says.

Separating fact and fiction.

Helping consumers separate sense from nonsense in health and medicine starts with education, and ideally, the strengthening of laws related to quackery and medical fraud, says Stephen Barrett, a retired psychiatrist and author who founded HYPERLINK "http://quackwatch.org/"Quackwatch.org, which aims to educate the public on health fraud, myths, fallacies and misconduct.

“It’s a good idea to try to bring up people who have the ability to determine what’s true and what isn’t, and to think logically,” says Barrett, who has been fighting against quackery for decades. Parents and schools can both play a role, he adds.

Today, there are still diseases for which the medical community simply hasn’t discovered cures. The multi-billion-dollar supplement industry exploits that same sense of fear and uncertainty that consumers faced in the late 1800s, Kang says.

“As long as that gap is going to be there, there is going to be quackery, and there is going to be snake oil,” Kang says. “And people just have to try as hard as possible to educate themselves and find sources where they can bounce things off of to make sure they’re not being victimized.”

Jordan Friedman is a freelance writer based in New York City. He has contributed to Fortune Magazine, USA TODAY, U.S. News & World Report and Mental Floss.

The terms "snake oil" and "snake-oil salesperson" are part of the vernacular thanks to Clark Stanley, a quack doctor who marketed a product for joint pain in the late 19th century.

“I love the story of Clark because he really is the quintessential snake-oil salesman—of course, literally, but also figuratively,” says Nate Pederson, co-author of the book Qauckery: A Brief History of the Worst Ways to Cure Everything. “I think that’s what’s interesting about him as a historical figure.”

Dissecting the term “snake oil”

Stanley—along with other medical fraudsters of his time—brought the terms “snake oil” and “snake-oil salesperson” into the mainstream vernacular.

“There was no evidence the [snake oil] did anything,” says Joe Schwarcz, a chemist and the director of McGill University's Office for Science and Society which aims to combat scientific misinformation. “That started the whole business of calling ineffective substances ‘snake oil,’ and we still have that today.”

Why is “snake oil” so widely used? Perhaps because it’s a lively term that conjures up an obvious connotation of greed and harm, as well as fear, interest and deceit. “There’s kind of no mistaking when someone says it, what they mean; there’s no nuance in the term,” Kang says. “And I think it harkens back to a very long cultural history that’s very anti-snake.”

As the field of medicine and laws have evolved since the early 1900s, the battle against misinformation has persisted. The American Medical Association (AMA) has been at the center of this fight. In the early 1900s, the AMA formed a Bureau of Investigation—originally named the “Propaganda Department”—to expose and combat medical quackery, or the promotion of unsubstantiated or fraudulent health claims.

Stanley—along with other medical fraudsters of his time—brought the terms “snake oil” and “snake-oil salesperson” into the mainstream vernacular.

“There was no evidence the [snake oil] did anything,” says Joe Schwarcz, a chemist and the director of McGill University's Office for Science and Society which aims to combat scientific misinformation. “That started the whole business of calling ineffective substances ‘snake oil,’ and we still have that today.”

Why is “snake oil” so widely used? Perhaps because it’s a lively term that conjures up an obvious connotation of greed and harm, as well as fear, interest and deceit. “There’s kind of no mistaking when someone says it, what they mean; there’s no nuance in the term,” Kang says. “And I think it harkens back to a very long cultural history that’s very anti-snake.”

As the field of medicine and laws have evolved since the early 1900s, the battle against misinformation has persisted. The American Medical Association (AMA) has been at the center of this fight. In the early 1900s, the AMA formed a Bureau of Investigation—originally named the “Propaganda Department”—to expose and combat medical quackery, or the promotion of unsubstantiated or fraudulent health claims.